International Booker Prize 2025: Kannada author Banu Mushtaq makes history with Heart Lamp

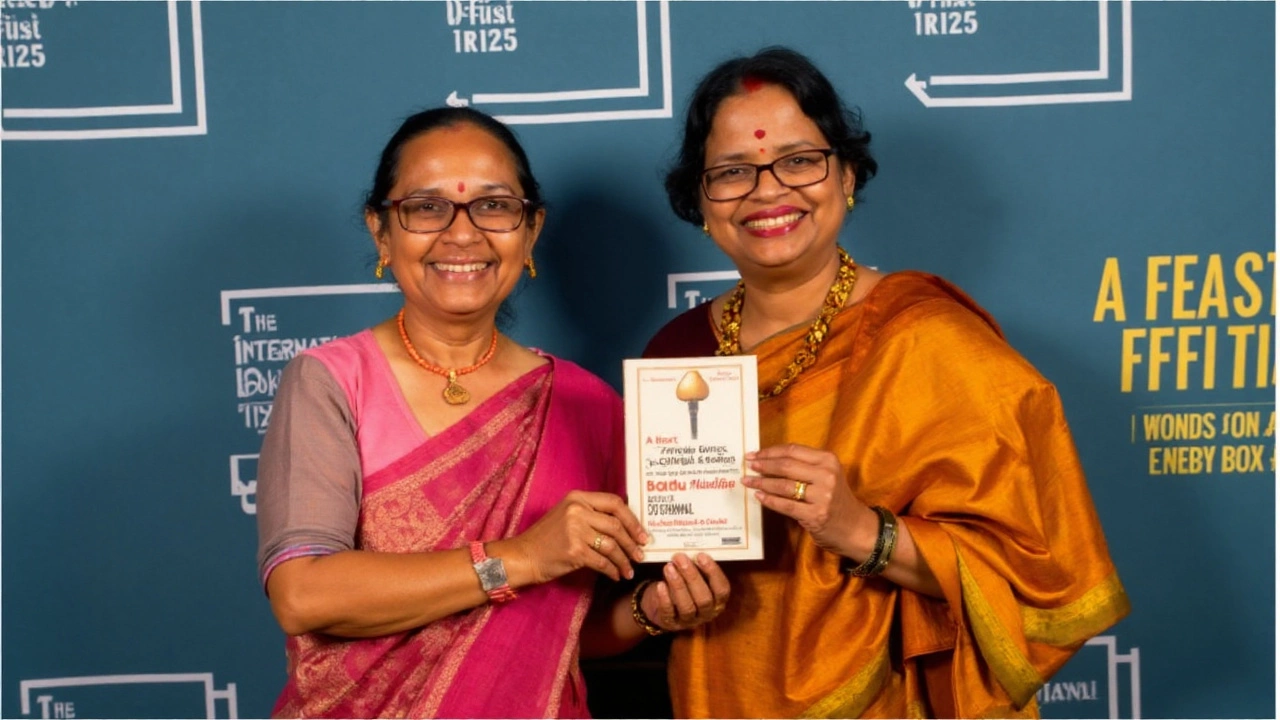

A short story collection in Kannada—carried into English by an Indian translator—has just outpaced a field usually dominated by novels. Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp: Selected Stories won the International Booker Prize 2025, making her the first Kannada-language author to take the award. Translator Deepa Bhasthi also made history as the first Indian translator to be named a winner. The prize was announced in May, and the book, published by UK indie And Other Stories earlier this year, has already started reshaping how publishers and readers look at Indian regional languages.

This win packs in a rare trio of firsts: a first for Kannada, a first for an Indian translator, and a first for a short story collection. For a prize that typically favors novels, that signals a shift. It says readers are ready for compressed, scene-by-scene storytelling where every sentence carries weight.

- First Kannada-language author to win the International Booker

- First Indian translator to win the prize

- First short story collection to take the award

The road to Heart Lamp

Mushtaq did not start out chasing literary prizes. She began writing at 29, fresh into motherhood and wrestling with postpartum depression. The stories arrived as a way to make sense of a changed body, a changed home, a changed self. That urgency never left her prose. Over the next three decades, she published six short story collections, a novel, essays, and a book of poems. Her work traveled across India’s languages—Urdu, Hindi, Tamil, Malayalam—and now into English.

The 12 stories in Heart Lamp were picked from six collections published between 1990 and 2023. Bhasthi started the translation project in 2022, not as a quick one-off but as a careful curation. The idea was to frame a body of work rather than a single book—tracking how Mushtaq’s voice moves over time while staying anchored to the same core concerns: women’s agency, the private cost of public rules, and the quiet ways people resist.

That mixing of decades shows. One story feels like a tight corridor where a woman calculates the price of speaking up; another opens onto a sun-drenched courtyard that looks warm until you notice who gets to sit in the shade. These are women at home, at work, at court, and at prayer—figuring out what can be bent and what must be broken.

Mushtaq’s twin training as a journalist and a lawyer runs through the collection. You see the reporter’s eye for detail: how a room is arranged, who brings the tea, who stands at the doorway and why that matters. You also hear the lawyer’s ear for power: how a rule is quoted, how a right is denied, how an exception becomes a habit. The result is fiction that reads as everyday life but hums with legal and social undercurrents.

Her reach was already visible on screen. The story Karinaagaragalu became Hasina in 2003, directed by Girish Kasaravalli, one of Kannada cinema’s most respected voices. The adaptation showed what readers already knew: even when Mushtaq writes about a single household, the implications spill outward into community and country.

Translation is the reason these stories now travel further. Bhasthi’s English is clean and close to the bone. She keeps the rhythm of coastal Karnataka without turning the page into a glossary. The vocabulary of food, kinship, prayer—often hard to move across languages—feels intact. She resists flattening. That restraint lets the humor land without explanation and the grief arrive without ceremony.

Heart Lamp is also a bet on the short story form itself. Each piece is a full world that ends while you still hear it echo. Taken together, the 12 stories have the sweep of a novel but with the intimacy of a diary, story by story, year by year.

Why this win matters

On the surface, this is a prize announcement. Beneath that, it’s a shift in who gets seen and how. Kannada is one of India’s major languages, with more than 40 million speakers. It has a deep literary tradition, the kind that repeatedly produces national heavyweights—names like Kuvempu and U.R. Ananthamurthy quickly come to mind. Yet for decades, English-language markets largely met Kannada writing through short excerpts or out-of-print translations. A Booker win changes the baseline. Suddenly, readers ask not “Is there anything in translation worth reading?” but “Where can I find more?”

The International Booker honors a book translated into English and splits the prize equally between author and translator. That equal split is not symbolic—it states outright that translation is co-authorship. Bhasthi’s win underlines a point practitioners have made for years: you cannot globalize a literature without investing in the people who build the bridge. Expect that to ripple through publishing schedules, grant programs, and university syllabi.

The jury, chaired by novelist Max Porter, praised Heart Lamp for its clear-eyed look at patriarchal systems and the everyday forms of resistance. That judgment lines up with how the book reads on the page. The politics are not loud speeches; they’re choices made after the dishes are washed. A door left unlocked. A signature withheld. A silence held longer than expected. The drama is domestic, but the stakes are public.

Media responses framed the book as both accessible and exacting—quick to read, slow to shake off. Reviewers noted how the tone shifts from wry to tender without breaking the throughline. It’s the consistency of vision that stands out: even when a story feels light, the foundations are solid.

For short stories, this is a watershed. Prizes often ask for “expansive narratives,” which can tilt the field toward novels. Heart Lamp shows that a collection, if shaped with intent, can deliver breadth through accumulation. Each new story doesn’t repeat the last; it refracts it. One narrative sharpens the next, and by the end you’re reading your own assumptions differently.

For Indian regional languages, the strategic impact is obvious. Editors now have a case study when they pitch Kannada, Tamil, Malayalam, Bengali, or Marathi books to English-language imprints abroad. They can point to sales that follow a prize, but also to the long tail: festival invitations, new translations into European and Asian languages, classroom adoption, and reissues of earlier work. That ecosystem matters more than the single headline.

There’s another quiet shift here. Stories set within Muslim communities in southern India, told without exoticism or apology, are not often the ones pushed to the front of global lists. Heart Lamp puts them there. The people in these pages are not metaphors. They are neighbors, colleagues, aunties, paralegals, bakers, and teachers. You recognize their frustrations even if you do not share their rituals. That is how fiction travels—by finding the common mechanics of a life and letting the specifics stay specific.

What do the stories actually look like on the sentence level? The prose is spare. Humor shows up sideways. A joke may be tucked into a description of a cupboard. Tenderness sneaks in through an argument about money. Scenes end before the moral can be underlined. That choice respects the reader. It asks you to supply the last inch yourself.

None of this erases how hard translation can be. Idioms bruise easily. Registers slip. Words for kinship and faith carry lifetimes in two syllables. Bhasthi’s approach seems to be to carry the load lightly: keep the syntax close to English while letting Kannada sensibilities run underneath. She doesn’t explain everything. She lets context do the work. That keeps pace and energy without turning the book into a guided tour.

The publisher matters here too. And Other Stories is known for backing translation and risk-taking fiction. That institutional trust—editing time, marketing muscle, patience with discovery—lets a book like Heart Lamp find its readers beyond the usual circles. Expect other houses to follow with scouting trips to Bengaluru and Mangaluru, and more calls to translators with regional expertise.

To understand Mushtaq’s range, it helps to track the professions and spaces that repeat across the book. Newsrooms appear, with their fast, cynical banter. Courtrooms appear, with their slow, procedural grind. Kitchens and thresholds do a lot of work—who sits, who stands, who serves, who speaks. Love is not missing, but it often has company: money, family reputation, a law that cuts the other way.

All of this began, remember, with a late start and a private struggle. Postpartum depression is not a biography footnote here. It’s the ground from which the early writing grew—the need to name what felt unsayable, then to keep naming it in different rooms, different years, different lives. That persistence gives the writing its steadiness. You trust a story more when you can feel what it cost to write.

If you’re new to Kannada literature, Heart Lamp is not a bad doorway. It is local without being closed, and global without being smoothed out. You learn the rhythms of a place—coastal humidity, the pull of faith, the bureaucracy of everyday life—through the decisions people make when nobody is watching. The collection doesn’t claim to speak for a region or a religion. It speaks for the characters it carries, which is the more honest ambition.

The numbers will come—reprints, foreign rights, reading lists. The deeper change will take longer: editors asking different questions in acquisitions meetings, translators getting earlier seats at the table, readers browsing with wider curiosity. That’s how a prize does its best work. It isn’t just a crown. It’s a door.